I started doing the #1000wordsofsummer challenge way back at the beginning of June. It was supposed to be 14 days of posts in a row but, well, that went out the window pretty fast. However I did commit to writing only about the history of photography as it relates to African Americans and I want to complete that goal even if it’s far outside the challenge window. This is post 10 of 14. Patrons get early access.

An interaction I had on Instagram this week is the spark behind this post. A vintage photo account that I follow posted a photo of a woman in blackface/brownface. Unfortunately, this is not uncommon. I’ve unfollowed numerous accounts for this very reason. I’m not posting the photo because I firmly believe these images shouldn’t be circulated. The photo wasn’t as old as you’d probably assume either—it looked like a digitized slide to me. Based on the living room furniture and hairstyles, I estimated 1970s or 80s.

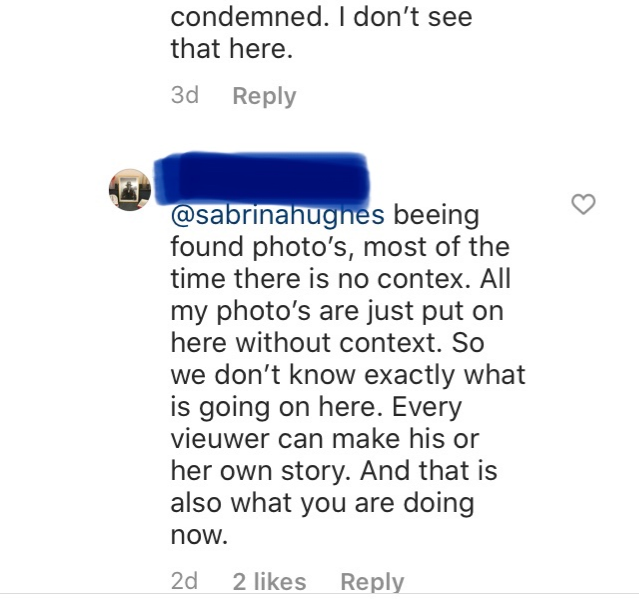

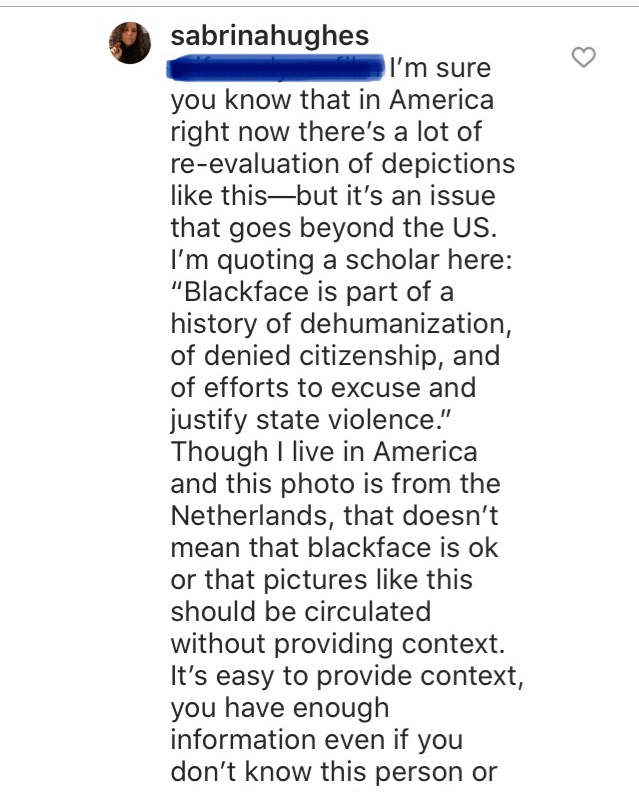

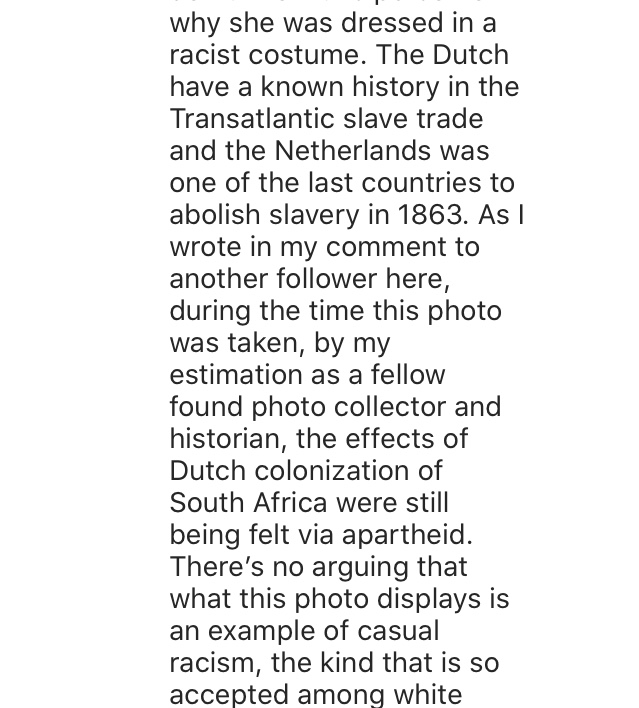

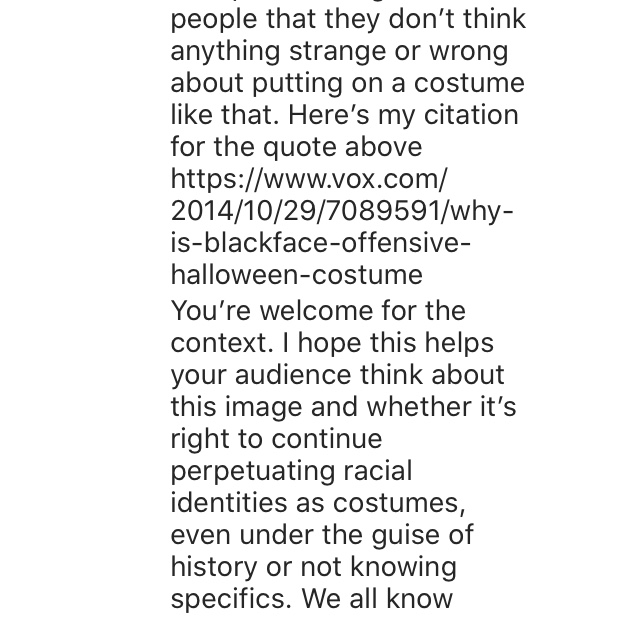

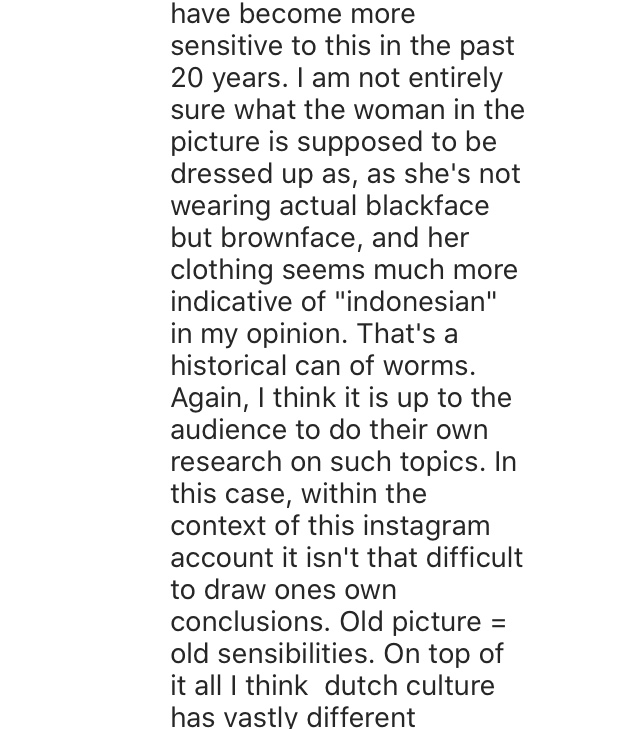

Here is the exchange between me and the account owner/vintage photo collector (redacted in blue) and some other person who chimed in (redacted in brown).

I stopped engaging with the rando in brown after his lengthy response because (a) he gave context which was what I was initially asking for (though I want to hear more about Indonesia obviously, bc I also know enough about that to know it is not somehow ok as he suggests), and (b) he really dug himself into a hole of complicity with his last couple of sentences, basically saying that *he* wasn’t offended, so neither should anyone else (which is essentially the problem with images like this being in circulation—the white guy doesn’t get to make those decisions).

Later I was thinking about an essay that I read in grad school (and one that I used to assign in History of Photo, but I realize I haven’t been able to get it in the last couple of semesters) called “Propaganda and Persuasion.” It’s attached here if you want to read it.

Scholar Estelle Jussim’s essay emphasizes the importance of contextualization for images because, depending on the history, personal beliefs, and experience of the viewer, the same image can be interpreted with completely opposite conclusions.

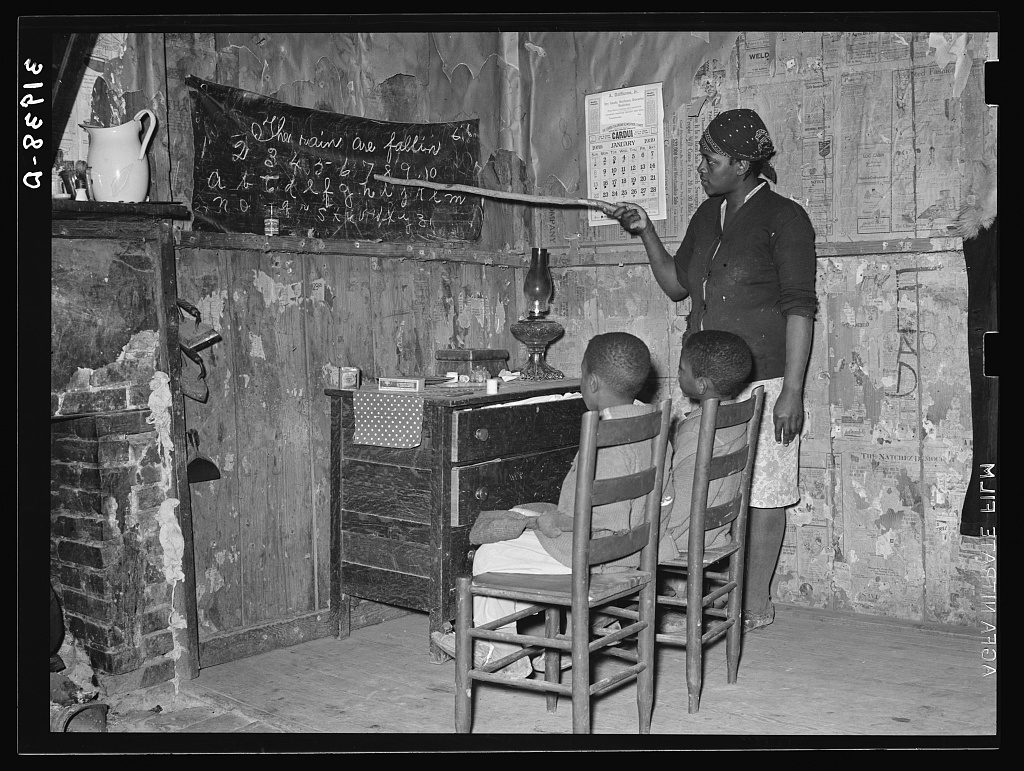

The image that Jussim uses to illustrate her argument is a photograph made by Russell Lee, who was a Farm Securities Administration photographer. The FSA photographers traveled the United States, especially the rural areas, to document the effects of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl on the vast expanses of the country.

In this photograph, a Black mother is teaching her children to read cursive letters and to recognize numbers. They are in their home, the walls of which are covered with newspaper. There’s a calendar on the wall and one overstuffed dresser with an oil lamp and some other things on top. The mother is standing, pointing to the slate or fabric on the wall with the kids’ lesson written in chalk. The children sit attentively in straight-backed chairs.

Jussim argues that depending on whether the viewer of this photo is on the left or the right on the political spectrum, they bring to it their own beliefs and assumptions and can justify that the photograph is supporting either of their views. For instance, she writes that a viewer who is more politically liberal may interpret the photo to have a sense of striving, that the mother is preparing her sons with an education that they are not otherwise guaranteed in rural Louisiana in 1939. It may be read as a document of the living conditions and educational possibilities faced by African Americans before the Civil Rights struggles in the 1960s. She suggests a viewer who is more politically conservative may draw conclusions from the state of the home and the sentence “The rain are fallin” that adult African Americans can’t identify grammatical errors that a white child of six already knows. They may see the state of the home as indicative of a failing on the part of the mother to improve her situation.

In Jussim’s essay (published in 1984), the photograph is called “Instruction at Home; Transylvania, Louisiana” which seems to have been the title that the photo was given by Roy Stryker, the head of the FSA Photography project. The Library of Congress has updated the title to what was on the caption card, which, from what I gather from their description, would have been what Lee originally captioned it before sending the photo and caption to Stryker for final editorial review. Lee’s title “Negro mother teaching children numbers and alphabet in home of sharecropper. Transylvania, Louisiana” is more descriptive, though regardless of how it is captioned, Jussim’s argument stands. The caption as Lee wrote it doesn’t take a position about how it is to be interpreted.

“One photograph verifies two entirely opposing ideologies,” Jussim writes. Both hypothetical viewers could point at portions of the photo that support the beliefs they already have. Essentially, an image alone isn’t enough to persuade someone. Text is key if the goal is to communicate one particular interpretation.

I think of another set of photographs that I personally misread because of first experiencing them without captions: Ansel Adams’ photos from the Manzanar concentration camp for Japanese-Americans. When I first encountered these photos, I was honestly disgusted. Adams visited the camp where American citizens were being held, having been forced to evacuate their homes and businesses, and took pictures of them smiling, playing baseball, and in general going about life in the camp as if it was normal. I was so angry! From just looking at the photos, I thought Adams was creating pro-internment propaganda to justify the US government’s extrajudicial imprisonment of thousands of citizens.

Baton practice, Florence Kuwata, Manzanar Relocation Center (1943), Ansel Adams

I found out later, from one of the very few studies of this set of photos, that Adams had actually intended them to be published with lengthy essays and captions that framed the injustice of their experience, but that they were persevering anyway. That’s still kinda a bs message BUT the captions that Adams insisted were published with the photographs contextualized them, and helped viewers understand why he made so many portraits of people smiling while imprisoned (I plan to write more about this entire moment—it’s in the queue). The captions were published in Adams’ book Born Free and Equal, but it’s entirely possible to run into these photos without the important contextualizing text on the internet (as I did) and to draw different conclusions about Adams’ goal with the photographs.

To return to my Instagram experience from this week, it is clear that the same photo of the woman in brownface for a party, sparked divergent interpretations. I thought it was irresponsible to put photos like this online without at least attempting to contextualize them as “something that used to be seen as ok by some people but that we should definitely leave in the past.” The owner of the account and the other commenter thought “the viewer can decide whether it’s offensive or not.” With images that perpetuate systemic racial inequality, stereotypes, and violence, that is simply defending the white supremacist gaze and ideology.

Family photographs are documentary photos too. We may not think of them that way, but they are. They document our individual rituals, ideologies, and beliefs. When we can see large sections of family photos from multiple decades, as collectors do, we can draw conclusions about the rituals, ideologies, and beliefs of a culture. Photos of white people in black/brown/yellow/redface exist in sufficient quantities and across various euro-originating (colonizer) nationalities that we can conclude that this practice was viewed as ok in the past, as that commenter said. But if we bring them with us into the present, and put them on the internet for the future, we’re bringing that past with us and giving it implicit approval that it’s still a little ok. We all know enough to know better.

0 Comments