I started doing the #1000wordsofsummer challenge way back at the beginning of June. It was supposed to be 14 days of posts in a row but, well, that went out the window pretty fast. However I did commit to writing only about the history of photography as it relates to African Americans and I want to complete that goal even if it’s far outside the challenge window. This is post 8 of 14.

____________

Frederick Douglass is probably a familiar name to many Americans, though I’m not sure his experience is taught with as much rigor and repetition as Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin, which made slave labor even more profitable for landowners and even worse for the enslaved laborers.

Douglass was enslaved at birth, which is what is part of what is meant by the term chattel slavery. Children inherited their status as enslaved individuals through the status of their mother. This is the custom that permitted ownership of African-Americans long after the import of humans from Africa was officially banned by Congress in 1807. In fact, it is only because by 1807 there were sufficient African-Americans already in the country to reproduce the labor force that the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves had enough support to pass. Even proponents of forced labor knew they didn’t need to continue the costly voyages from Africa to continue to perpetuate generational enslavement in this country. (For more on this, I highly recommend the book The Half has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E. Baptist)

Frederick Douglass was born sometime in February 1818 according to the records of the landowner who kept his mother imprisoned. He was separated from his mother as an infant, but had the minor fortune to be placed with his maternal grandparents with whom he lived until he was 6, at which point he was moved to a plantation to begin life as a laborer. Around the age of 12, Frederick surreptitiously started teaching himself to read. The landowner’s wife had taught him the alphabet, however the landowner put a stop to all of her efforts to tutor Frederick, saying that education and slavery were incompatible. I mean, he was not wrong. As Frederick improved his skills at reading and writing, his ideas about the practice of enslaving humans for forced labor took shape.

At some point, when Douglass was moved to another plantation, he began teaching other laborers to read, holding weekly Sunday school lessons. This went unnoticed by their jailers for about 40 weeks, but when some found out about it, they terrorized the meeting to an extent that the workers were afraid to meet again. Douglass was then moved to another plantation (at this point he was only 16 years old) whose foreman was known for the brutal treatment and physical breaking of workers’ spirits to get them to obey. By his own account, Douglass was broken in body, soul, and spirit, but he still found the will to fight back one day. This must have been a hell of a fight because the foreman never beat Douglass again after that.

At 20, in 1838, Douglass escaped his captivity in Maryland and made it to the abolitionist stronghold of Philadelphia by way of Delaware, then continued on to New York City to put more miles between him and his captors. Douglass married Anna Murray, a free woman he had met in Baltimore, and the couple moved to Massachusetts. Douglass became a world-renowned orator and abolitionist. Having been enslaved, he could speak to the experience in a way that white abolitionists could not.

So all of that is background so we can talk about Douglass’ high esteem for photography as a tool for Black liberation. Photography was released into the world in 1839, just one year after Douglass escaped captivity. It was a brand new mode of visual representation. We are so accustomed to photography in our lives that it’s hard to imagine what it would have been like to experience it for the first time.

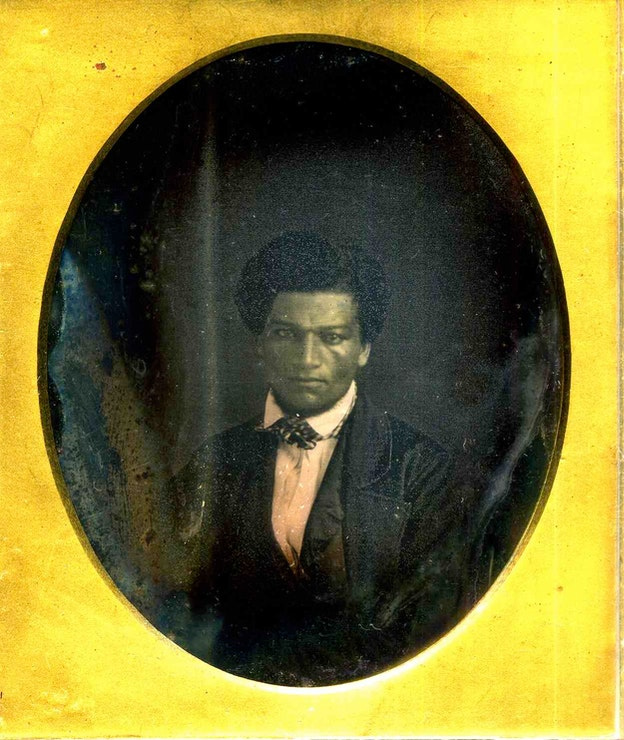

Frederick Douglass, 1841

What photography does that painting, drawing, etching, or any other mode of visual representation that existed at the time cannot do is present an image with perceived neutrality and truthfulness. I say perceived because as I have said before and will say again, photographs are not neutral nor are they necessarily truthful. However, we do assign them, even now, an aura of operating within the realm of reportage rather than art. The mediation between a photographer and a photograph is different than that between a painter and a painting. The photograph (especially at this early time in the medium’s development) revealed something that had been in front of the camera and had thus been recorded as seen by the camera. A painting (or drawing, etching, whatever) revealed the skill of the artist at rendering an image of something from nothing other than their artistic skill and interpretation. I hope that makes enough sense to continue on for now. I could easily write a couple thousand words expanding this idea, and I probably will in the future, but I don’t want to lose track of Frederick Douglass.

Among his essays and speeches, Douglass wrote three about photography: “Lecture on Pictures” from 1861, “Age of Pictures” (1862), and “Pictures and Progress” (1864-1865). It is doing a serious disservice to the philosophy behind these lectures to try and summarize them in a short post like this, so I won’t. Suffice it to say that Douglass grasped the inherent ideological power of photography as a tool for self-representation and liberation from the start. A relatively recent book (2015, which in the world of academic scholarship is still pretty recent) Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, reminds contemporary historians of Douglass’ passion for photography—not as the operator of the camera, but as a sitter, as the person whose portrait is being made. The authors approach their research with an important question: “[B]ecause his photographic passion has been almost completely forgotten, historians have missed an important question: why was a man who devoted his life to ending slavery and racism and championing civil rights so in love with photography?”

The historians who researched and wrote that book identified 160 distinct photographic portraits that Douglass had sat for during the part of his life that intersected with the advent of photography. That number may not feel like much to us here and now, but it is worth stressing that in the 19th century, not everyone had ONE photograph of themselves. If you’re fortunate to have a few generations of your own family photographs, you can test this yourself. It wasn’t until the 20th century that the kind of photographic documentation of our lives that we’re accustomed to became the norm.

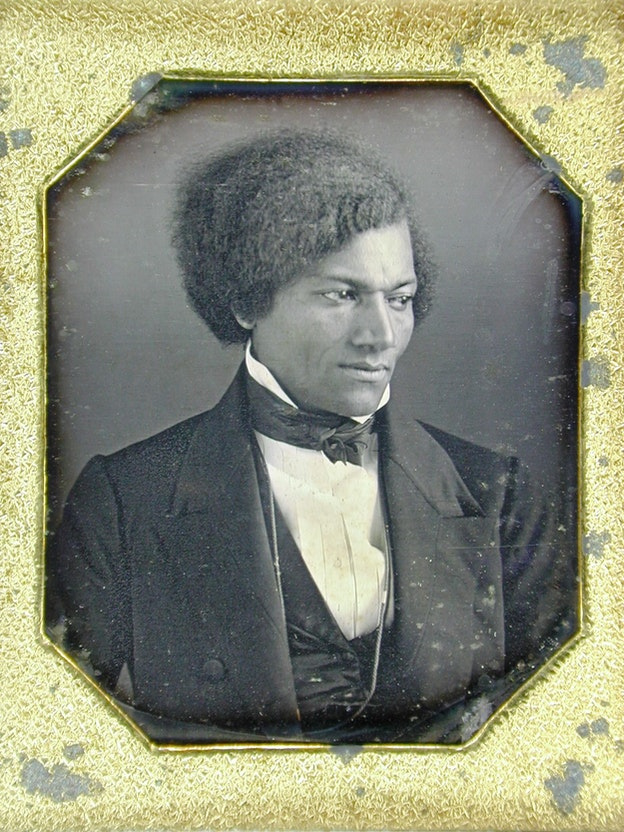

Frederick Douglass, May 1848 (he gave this portrait to Susan B. Anthony)

Douglass sat for portraits as often as possible while on his lecture tours, recognizing that photography, especially as it became cheaper and more accessible, would spread his abolitionist message as effectively (if not moreso) as his essays and lectures (which had to be attended or read). He saw photographs as tools of public relations, as the way to circulate a public persona OF HIS OWN CREATION AND CHOOSING. Once a portrait of someone is published, Douglass wrote, “His position is defined, and his whole persona must now conform to, and never contradict, the immortal likeness or unlikeness in the Book” (“Lecture on Pictures” (1861), published in Picturing Frederick Douglass). Portraits can stand in for the values that someone holds, and can serve as mnemonic devices for those very values. He also recognizes that the publication of one’s portrait and the creation of a persona means that the person is creating a responsibility to maintain those values that they want to stand for.

He knew photography was a way to actively counteract the dominant visual representation of African-Americans through harmful visual stereotypes. The more photographs of Douglass that existed, the broader and deeper the visual representation of Black citizens became. Each new portrait (or reproduction) became a new object that had the potential to negate a stereotypical image once it was in circulation.

Douglass developed his own visual style for how he wanted to be photographed (his brand, if you will) and maintained that style over decades. Unlike the popular conventions of early portrait photography, Douglass eschewed the decorative backdrops and other props that photo studios had on hand. Instead he preferred a plain background that didn’t compete with or draw attention away from his face. He often looked directly into the lens, also an unusual convention at the time. He is making eye contact with everyone who views the image, a connection that can be made across time and distance. Then, as now, photographs that were attempting to aid the preservation of Black lives often depicted the pain and suffering that individuals endured. Douglass wanted people to focus on his face, on his humanity, on his personhood.

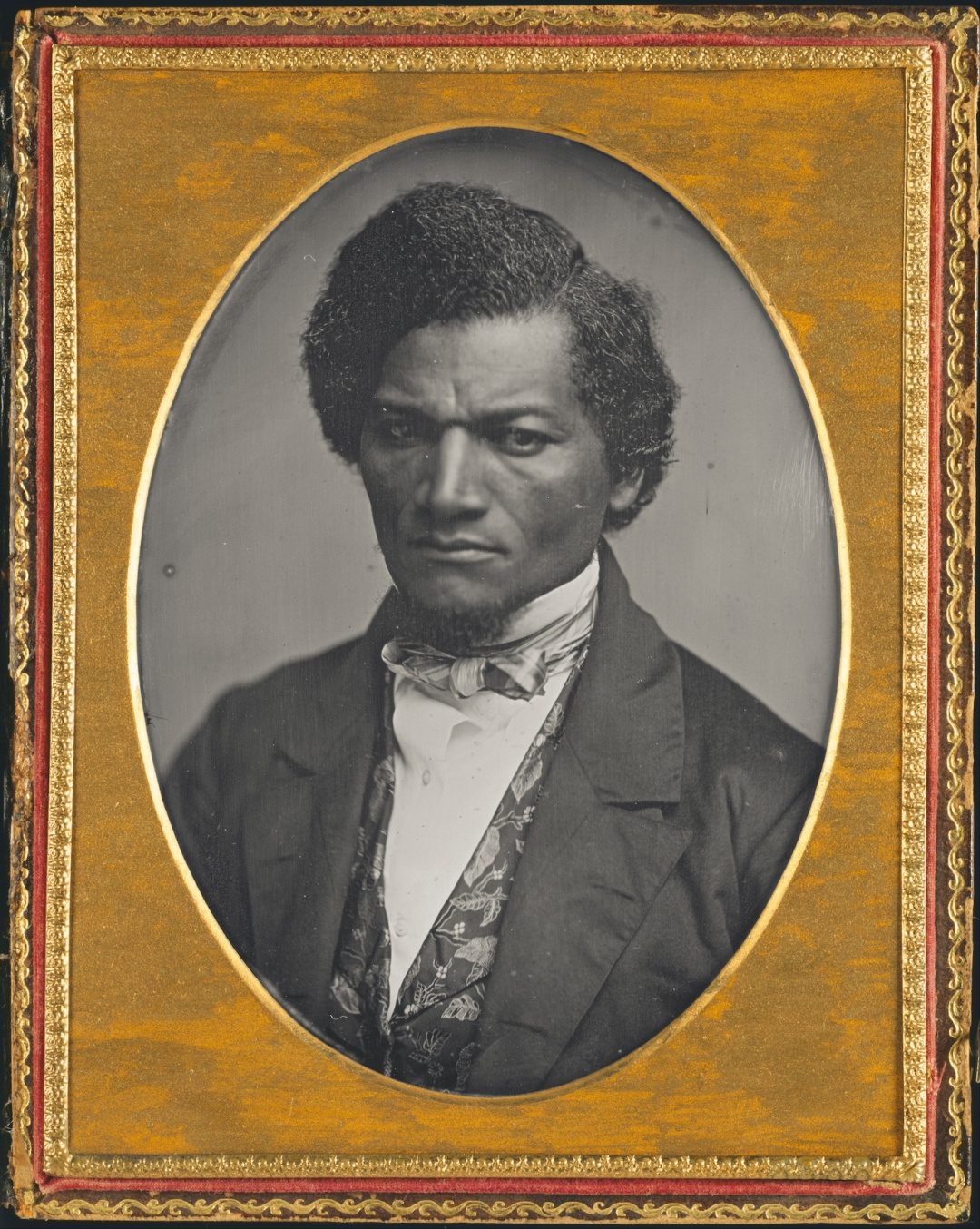

In his portraits, he adopted a neutral expression that, as he aged, refined his message, and became more outspoken about civil rights, became more stern, as if a bulwark for the message. He never smiled in his portraits, and there was an ideological reason for this too. “He did not want to be portrayed as a happy slave,” John Stauffer, a fellow author of Picturing Frederick Douglass, told NPR. “The smiling black was to play into the racist caricature. And his cause of ending slavery and ending racism had the gravity that required a stern look.” The happy slave stereotype, like that of the brute (and countless others) furthered the white supremacist agenda. In particular, this one perpetuates the idea that African Americans needed paternalistic looking-after by white people, and that their captors were actually their caretakers. Looking at the body of portraits, Douglass’ somber expression communicates such a variety of emotions and states of being. This portrait below is a favorite of mine. The expression I see in his face is that of persistence and determination no matter what.

Frederick Douglass portrait made sometime between 1847 and 1852

The photography marketing machine had not yet solidified the idea that photographs were objects that would communicate generations into the future, to uncountable generations of descendants, yet Douglass knew. Further, he knew the particular importance this would have for African American families. “It is evident that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations. The family is the fountainhead of all mental and moral influence. And the presence there, of the miniature forms and faces of our loved ones, whether separated from us by time and space, or by the silent continents of eternity, must act powerfully upon the minds of all. They bring to mind all that is amiable and good in the departed, and strengthen the same qualities in the living” (“Lecture on Pictures” (1861), published in Picturing Frederick Douglass). For Douglass, portraits could be educational tools for future generations.

It is worth noting that Douglass began sitting for portraits during a time when photography was not really suited for portraits. From the announcement of photography in 1839, people wanted to be able to create portraits, however at that moment it was not yet possible since even in strong light, plates needed to be exposed for three to fifteen minutes.

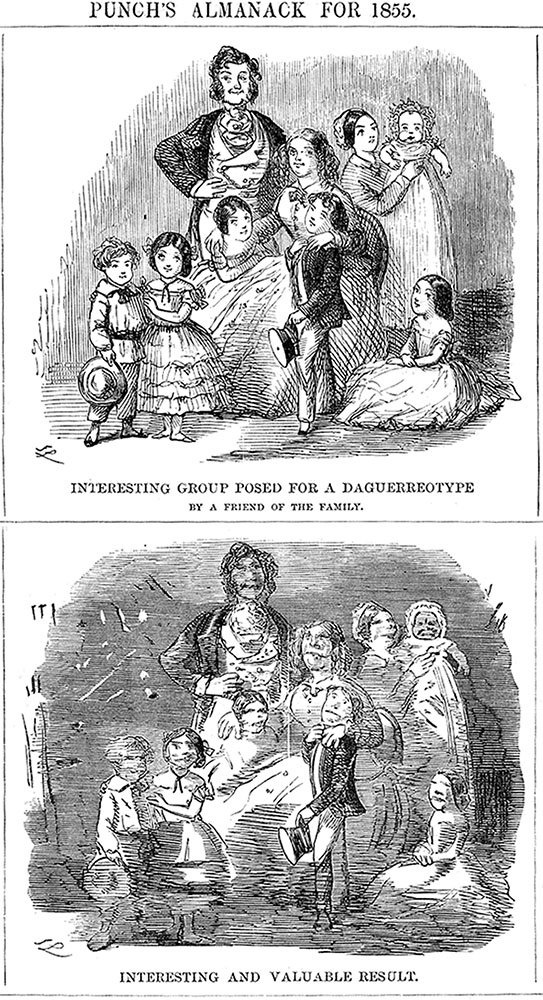

As more practitioners began trying new chemistry and making lenses that allowed in more light, portraits became possible, however they were still extremely uncomfortable for the sitter and often resulted in disappointing non-idealized portraits.

Yet photographic portraits did not really start to live up to the desires of the sitters for quite a while, as the comic above from 1855 illustrates. Douglass was sitting for portraits long before that. The earliest known portrait is the daguerreotype above from 1841. How long did he have to sit still for that image? Likely between 15 and 30 seconds, possibly more, but certainly not less.

It is my fervent belief that Frederick Douglass would have LOVED selfie culture, and honestly I would characterize all of his portraits as selfies because of their self-conscious creation and intent to be widely circulated. I would die on this hill, but honestly I don’t think anyone would disagree.

0 Comments