I’m doing #1000wordsofsummer challenge and I’ll be writing only about the history of photography as it relates to African Americans. This is post 6 of 14.

All pledges from Patreon and all proceeds from sales on thepicurious.com during June are being donated to the Fines & Fees fund of FRRC (Florida Rights Restoration Coalition) to help re-enfranchise voters who have served felony sentences.

As of today 6/10, we’ve raised $111.93. I have a 2:1 matching donor for any funds raised through NOON on Friday 6/12. That means for every $1 donated, $2 will be added to it, tripling your impact. If you’ve been waiting to buy yourself some art, this is the time to do it–or if you just want to contribute a little more to get in on the match, message me.

___________________________

Forgive me for again taking a few days to finish this thought. This is post 6 and it continues a historical thread that I began two posts ago.

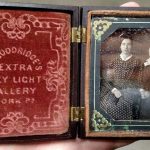

When I thought of this line of history to tell, I thought I could do it all in one post, but here I am in the third one and will probably go well past 3,000 words total on this story that started with Glenalvin Goodridge.

In the first post, I introduced you to Glenalvin Goodridge, a Pennsylvania photographer who was among only five or six African Americans to be practicing the new art professionally before 1850. Glenalvin’s life took a turn when he was indicted and sentenced for assault. His accuser was a young white woman. After serving a shortened sentence, having been eventually pardoned by the governor, he died of tuberculosis that he had contracted in prison.

In the second post, I tried to give some context to Glenalvin’s case. That was a hard one to write because I had to introduce a persistent stereotype of African American men, the Brute, who is imagined to be a particular danger to white women. Maybe only a danger to white women. This is a stereotype, not truth. And in that post I located the stereotype as arising only after, and perhaps as a response to, black individuals and communities building wealth. I ended with the terror campaign waged on the Greenwood District in Tulsa in 1921 by city officials in collusion with the KKK and other white citizens who saw the District’s relative autonomy as a threat. The connection here is that the event that sparked the action of the Tulsa Massacre was the accusation that a young black man had assaulted a young white woman.

This, the last post in this short historical thread, is the hardest one to write because it is about the larger terror inflicted on African Americans during apartheid in the United States (1877 to 1965) by the threat of extrajudicial torture and murder in the form of lynching. This has to be discussed because photography played a crucial role in perpetuating this psychological torture nationwide. I would argue, as many do, that the terror continues with a new form of disseminating the graphic images that constitute psychological torture when black individuals are publicly executed by state apparatus.

I’m not going to show any of these images, either historical or current. You all know how to google if you want to see them.

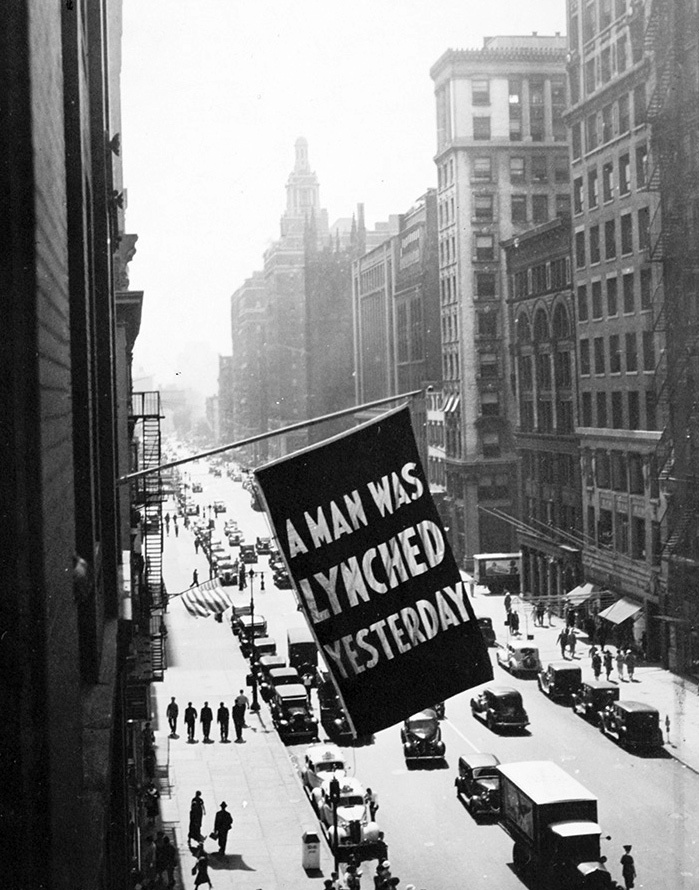

This flag was flown outside the NAACP headquarters in Manhattan between 1920 and 1938 after news of a lynching. The practice ended because the landlord threatened to evict them, not because lynchings ended in 1938.

First, let’s talk about the status of photography and its mass production and dissemination starting in the late 19th century. To return to the start of this historical thread, Glenalvin Goodridge was a studio portraitist very early in the invention of the medium. Photography was invented and the technology was released to the public in 1839. Glenalvin was practicing through most of the 1850s. At this time photography was still rather rarified. If you were of the upper class, you may have had your photograph made once or twice during your lifetime. It was still cost prohibitive to many people.

Kodak changed that with the introduction of the Kodak no. 1 in 1888. This was aimed at consumers of all classes, and it was with the introduction of this line of camera, which used rolled film rather than individual plates, that photography was marketed as something that should be part of our daily lives. With the Kodak, we record special events, family milestones, or just everyday life.

The first photo postcard was sent through the mail in 1899, and in 1902 Kodak standardized the form by creating a preprinted card back, the front of which was treated with photo emulsion. This marked the *moment* for mass production of images on postcards. Itinerant photographers traveled from town to town to document places and sell these images back to the residents so they could show far flung family where they lived and what life in their town was like.

“Local entrepreneurs hired them to record area events and the homes of prominent citizens. These postcards documented important buildings and sites, as well as parades, fires, and floods. Realtors used them to sell new housing by writing descriptions and prices on the back. Real photo postcards became expressions of pride in home and community, and were also sold as souvenirs in local drug stores and stationery shops.” —Old House Journal (via Wikipedia)

In 1903, Kodak introduced the No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak to consumers. It was designed for postcard-size film, meaning that anyone could take a snapshot and have it printed on postcard backs when they sent it to Kodak to be processed. Postcards were popular and anyone could make them.

Ok. So. Did you know about the popularity of lynching postcards?

They were popular. Lynching postcards were in widespread production for more than fifty years in the United States. What does “widespread production” mean? Like, what is the number of distinct postcard images? I don’t know. I’m not sure that number has been counted, or if it can be since postcards were both mass produced and created by ordinary people. They were collected as souvenirs, mailed across the country (sometimes with mundane messages that had nothing to do with the violence on the other side of the card), and sold in town drugstores.

Again, I’m not going to show any of these images. They are barbaric. I’m also not going to describe them, except to say that a common characteristic of these images is a sea of white faces looking, pointing, eating, laughing. If you would like to read descriptions of the images without seeing pictures, this is a good start. And if you would like to see the images yourself, you need only to google the phrase.

Let me take a moment to define terms which is an important step right now. What is a lynching? It is premeditated extrajudicial public murder by a group. In the US, it is synonymous, I think, with the method most often used, which was public hanging. Lynching is a manifestation of mob violence for the purpose of social control. There is always an element of public spectacle for maximum intimidation.

Mob actions enforced white supremacy and were systematic terrorism. Lynching attacks on African Americans, especially in the South, increased dramatically in the aftermath of Reconstruction, after slavery had been abolished and freed men gained the right to vote. Nearly 3,500 African Americans were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968. A 2017 study found that exposure to lynchings in the post-Reconstruction South “reduced local black voter turnout by roughly 2.5 percentage points.” There was other violence directed at blacks, particularly in campaign season.

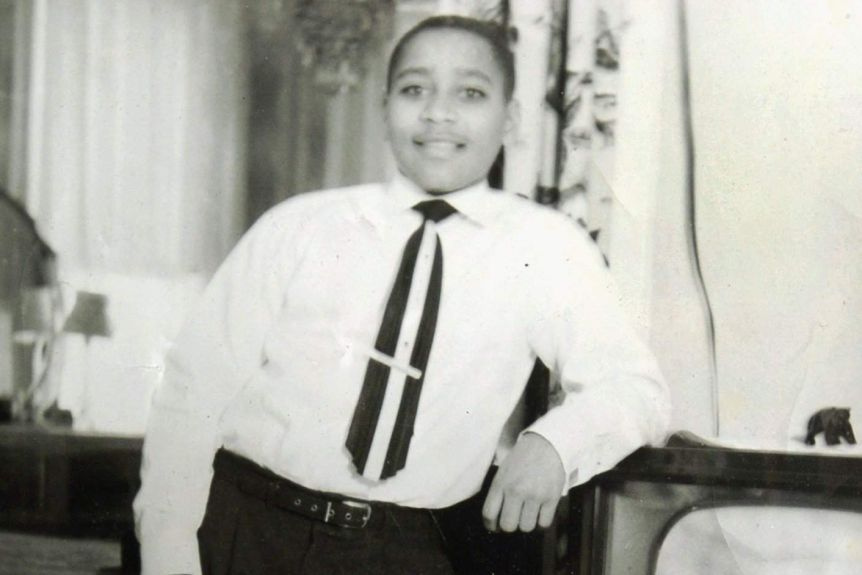

Emmett Till, December 1954

Maybe some of you have heard the name Emmett Till, but I’m finding that a lot of people don’t know this story. Emmett was a 14-year old boy who was visiting family in Mississippi. He was lynched after a white woman said he whistled at her. This was in 1955. His killers were tried and found not guilty (by an all-white jury) in the same year. In 1956, knowing they were protected against being retried for the same crime (double jeopardy), they admitted in an interview with Look magazine that they had murdered the child. Emmett’s accuser, Carolyn Bryant, later admitted that she had fabricated a large part of her interaction with him.

Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, insisted that his body be returned to her in Chicago not buried in Mississippi. She held an open-casket funeral and invited representation from the press. In the lid of the casket, she had pinned two photos of Emmett that had been taken at Christmas the previous year, and one photo of the two of them together. She said “There was just no way I could describe what was in that box. No way. And I just wanted the world to see.” (cw, there is a photo of Till’s body in the casket under the heading “Funeral and Reaction”) Tens of thousands of people lined the street outside the mortuary to view Till’s body and mourn.

Photographs of his mutilated body circulated around the country, notably in Jet magazine and The Chicago Defender. According to The Nation and Newsweek, Chicago’s black community was “aroused as it has not been over any similar act in recent history.” Time later selected one of the Jet photographs showing Mamie Till over the mutilated body of her dead son, as one of the 100 “most influential images of all time”: “For almost a century, African Americans were lynched with regularity and impunity. Now, thanks to a mother’s determination to expose the barbarousness of the crime, the public could no longer pretend to ignore what they couldn’t see.”

I would make a strong argument, though, that they had seen it, through postcards. The photo of Emmett’s body is so striking because it re-humanized him. The postcards turn victims of lynchings into objects. Photos of Mamie and her son’s unrecognizable body remind “the public” (i.e., white people) that Emmett had been a living child.

Lynchings were made illegal (like————shouldn’t extrajudicial killing be illegal by definition? But apparently not) in 2018 (!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!) and are now designated a federal hate crime. In 2018, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice was opened in Montgomery, Alabama, a memorial that commemorates the victims of lynchings in the United States.

But we’re not done yet.

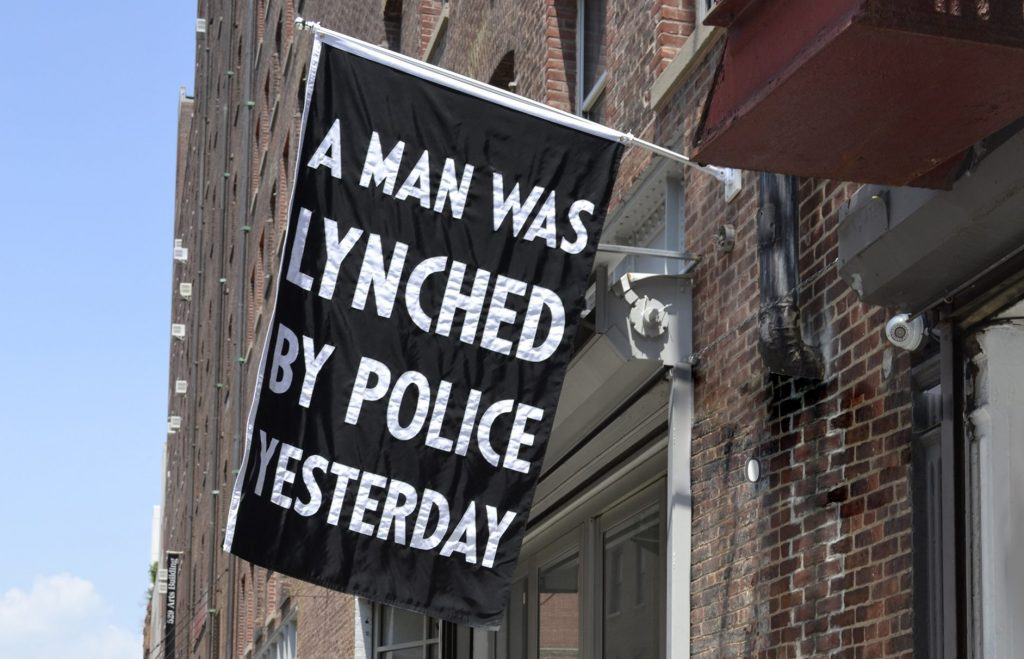

Artist Dread Scott reprised the famous NCAA flag after the 2015 shooting of Walter Scott

Many of the murders of African Americans at the hands of police have been called lynchings. In recent memory, I first heard the term used after 18-year old Michael Brown’s body was left lying in the street for hours after he had been lethally shot. That was in 2014.

Facebook Live launched in 2016 and since then we have seen numerous acts of heinous violence enacted live. In 2014 and earlier, social media companies contracted with other companies to have humans moderate all media that was submitted to post. In this WIRED article (again, from 1,000 years ago in 2014), one company, Whisper, describes its work as “‘active moderation,’ an especially labor-intensive process in which every single post is screened in real time” flagging “pornography, gore, minors, sexual solicitation, sexual body parts/images, racism.”

The murders of Sean Reed, Philando Castile, Roosevelt Rankins, Jr. , and most recently George Floyd were all broadcast on Facebook Live which begs the question—is this type of human-judgement based content moderation still practiced, or is it now all left up to the algorithm? And what types of violence are permitted either by the human mods or the algorithm? Why is violence against black bodies by police permitted to stay on the timeline? Conversely, if they were less visible would we have the calls for police accountability that we have today?

Extrajudicial killings by a group with the purpose of terrorism and intimidation and a core element of public spectacle—this is the accepted definition of lynching. What postcards did for white supremacy in the apartheid era, social media and big tech algorithms do today.

_______

NB: I didn’t provide links for some of the citations for this essay because the source (Wikipedia) shows numerous disturbing images, but a main source is the Wikipedia entry for Lynchings.

0 Comments