I’m doing #1000wordsofsummer challenge and I’ll be writing only about the history of photography as it relates to African Americans. This is day 2; patrons get early access and it will be public one day later.

Hmm well, that escalated quickly. If you haven’t yet watched yesterday’s Rose Garden proclamation, do. And listen for the flash bang grenades going off during the speech at the 34 second mark. Also, watch the video of what was happening during the speech in Lafayette Park in front of the White House–police in riot gear rushing the crowd of demonstrators to clear the way for the most awkward photo op ever–all of which you can conveniently see concurrently in this broadcast where Anderson Cooper completely DRAGS the president in a rare moment where he let his cool guy mask fall. I learned this morning that the secret service also ejected the cleric from the church so this could happen. Cool cool cool.

Ok, ok, ok, you all are here for photography.

Let’s learn about Gordon Parks.

You probably know this photo taken by Parks.

American Gothic, Washington D. C., 1942

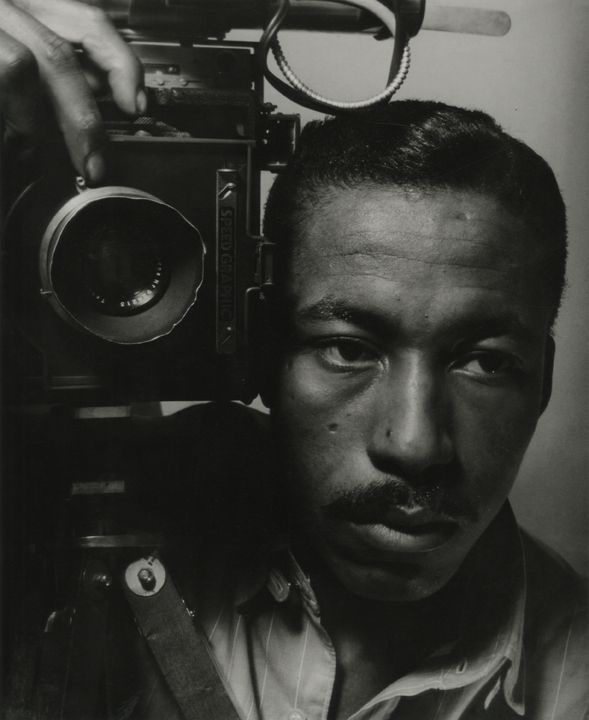

Here’s a self portrait because let’s be real this man could work both sides of the camera.

Untitled (1940)

Parks began his career as a photographer for a department store in St. Paul, Minnesota. He then began engaging with local newspapers, and documenting Chicago’s impoverished South Side. For this series of pictures, he was awarded a Rosenwald Fund fellowship of photography, which is how he came to be the only black photographer on the Farm Security Administration team. The photo of Ella Watson, above, was made while he was working with the FSA.

To my knowledge, Parks was the only FSA photographer to document the plight of the urban poor during the Depression. Perhaps this was because he joined the project in 1942, well into the documentary initiative that had begun in 1935, during the Dust Bowl (by 1943 the FSA photography project was folded into the Office of War Information), but more likely Parks documented the urban poor because as a black man in 1942, his freedom of movement was limited.

There are actually three projects by Parks (AT LEAST!) that relate to this particular historical moment, but today I want to share with you photos that he took in Montgomery, Alabama in 1956. This assignment was for LIFE, which hired Parks as the first African American staff photographer and writer in 1948.

At Segregated Drinking Fountain, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

LIFE asked Parks to go to Alabama several months after the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott to document what life was like under apartheid in the American south during a time when the persecution blacks endured daily was reaching a tipping point.

Parks shot this assignment in color, which was not his typical style at the time. To us now, black and white gives us the feeling of something being old or old-fashioned, but then black and white was the visual language of serious photography. Color photography, both in art and in news, was seen as distracting. Color photography was generally the preferred medium for family photos, not for reportage.

Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother Window-Shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

Choosing to create this photo essay in color at this time, 1956, signals an immediacy within the photos. In this instance, Parks’s choice to use color slide film may have been to heighten the sense of reality experienced by viewers. Television didn’t start broadcasting in color until the 1960s, so to see photographs in color would likely have been attention-grabbing to viewers. For readers of LIFE, the photos would have been difficult to ignore.

Upon arriving in Mobile, Parks was met by Sam Yette, a young black reporter who had grown up there and knew the area, and a white chief of one of LIFE’s southern outposts, Freddie. Freddie was supposed to be there to support Parks and Yette while they settled in and began to find a story, but Freddie was not trustworthy. First he told Parks that there wasn’t enough segregation in Alabama to merit a story (as if there are degrees of segregation). Freddie then put Parks and Yette in touch with someone who was supposed to “protect” them in case of “trouble.” This person turned out to be the head of the local White Citizens’ Council, which is right up there in hatred and persecution of blacks with the KKK. Parks and Yette left Mobile via back roads.

Outside of the cities, Parks found the person whose family would be the focus of the photo essay. Willie Causey and his family had reached a certain level of financial success for a black family in Alabama. Willie, a sharecropper, and his wife Allie, an elementary school teacher, had saved enough money to buy a used refrigerator and a car. Parks and Yette spent time with the family and photographed them at home and at work–they even stayed with the Causeys through the assignment, sleeping on their front porch. The photograph below is a portrait of Allie’s parents.

Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

LIFE wanted Parks to document evidence of the “separate but equal” edict, which you can see in many of the photographs here.

Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

Parks’s photos were published in the September 24, 1956 issue of LIFE. The Causey family was targeted by white supremacists after that publication. Their property and possessions were looted and they fled their home in fear of their lives.

According to the Gordon Parks Foundation, “Parks made sure that the magazine provided them with the support they needed to get back on their feet (support that Freddie had promised and then neglected to provide).”

I’d love to know more (and in less euphemistic language) about that negotiation between Parks and LIFE, and also where they Causey family ended up, how far from their home they had to move to feel safe from terrorists, and if that thug Freddie kept his job as head of a southern LIFE office. Honestly, probably. And even as Parks recounted this whole experience in later memoirs and interviews, he only referred to the man as Freddie, to protect Freddie’s family from possible violence (which, CLEARLY would have come from the white supremacists for aiding black reporters).

Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956

I have so much to say about Parks. His photos are so important and even moreso because he had such a huge platform (LIFE magazine, published weekly, with a peak circulation of 13.5 million copies per week, was only one of the major publications that he worked with). Like many black photographers, then and now, Parks knew the importance of photography: “The camera is my weapon against the things I dislike about the universe and how I show the beautiful things about the universe.”

0 Comments