In my last post, I introduced my art project The Picurious. I want to follow that up with a discussion of photography’s representation problem and how I’m tying to diversify the imagery of people represented in that project.

If you clicked through to look at some of the photos I’ve been sharing on The Picurious, you may have noticed a lot of white faces looking back at you.

The problem of underrepresentation of people of color in visual media is neither new nor unique to photography. However, I would argue that photography has played a unique role among the arts in the social subjugation of people of color in the United States.

I do several lectures on this topic in my undergraduate History of Photography course because it’s important to me to teach students that media is not neutral.

As a medium that purports to represent unmediated reality, photography has the potential to be dangerous when oppressive groups use photography as evidence for false representation, ultimately resulting in the subjugation of other people. To learn more about this, I recommend the excellent documentary Through A Lens Darkly.

As photography can be a weapon wielded to create a false narrative through images, it can also be just as powerful for those same underrepresented groups to control the production of their own image. Among the African American community during apartheid in America in the guise of “Jim Crow” laws, photography was the most important activity they could practice. Photography gave each individual the ability to control their representation to themselves and their friends and families. For more about this, I recommend reading bell hooks’ “In our Glory” which I’m linking to here.

From a commercial standpoint, black consumers were largely ignored by the corporations creating photography equipment. Until well into the 20th century, brown skin tones could not be accurately represented by the film emulsions that created colors from filtering light only into its red, blue, and green components (yellow is needed to approximate darker skin tones). It was only after commercial sellers of chocolate, wood furniture, and horses lobbied the film companies that they changed their film stock. For more on this, read “Teaching The Camera to See my Skin” by Syreeta McFadden. It is enlightening.

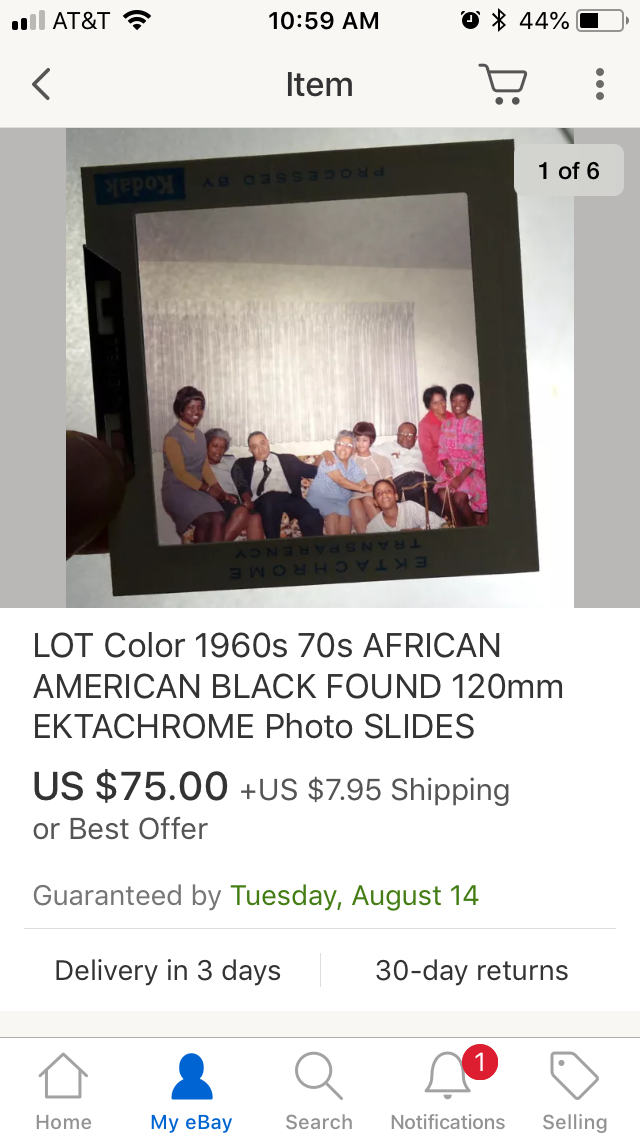

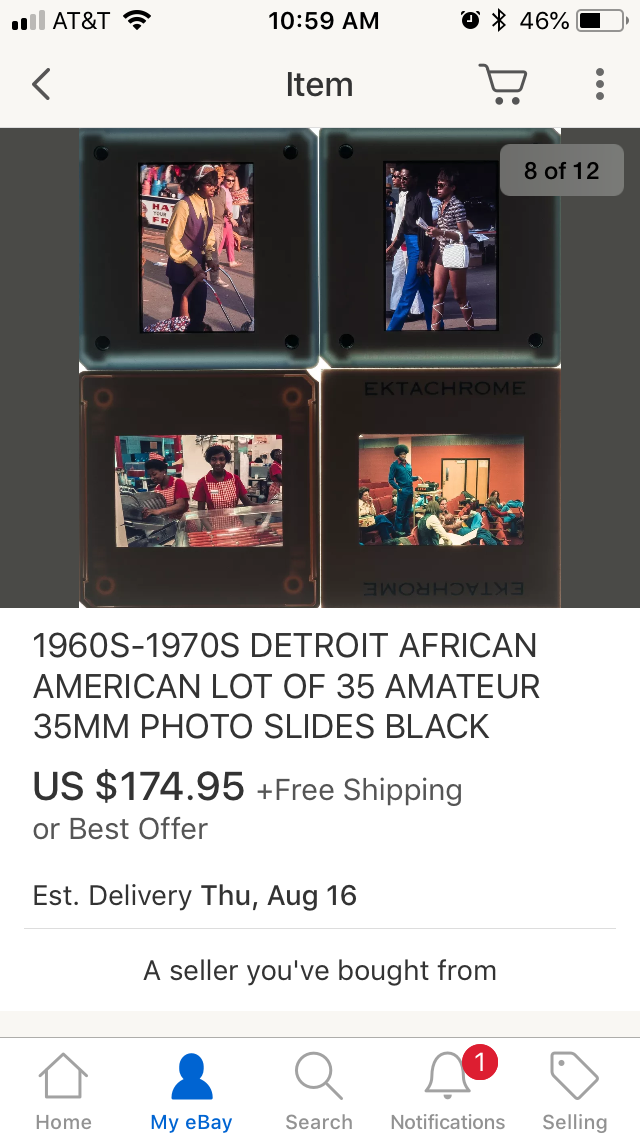

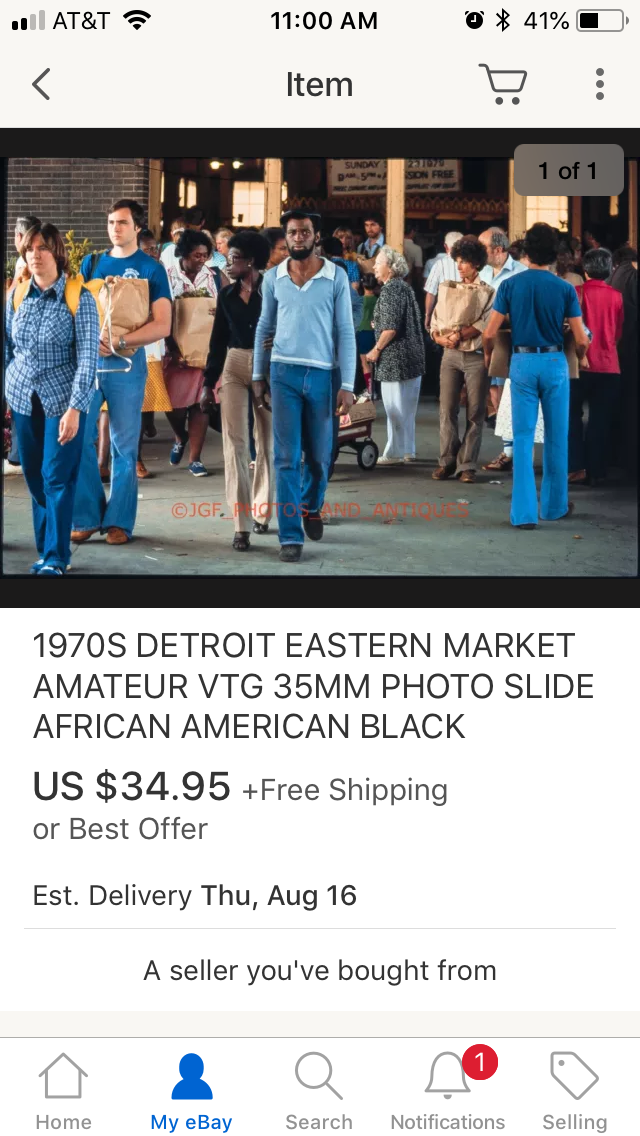

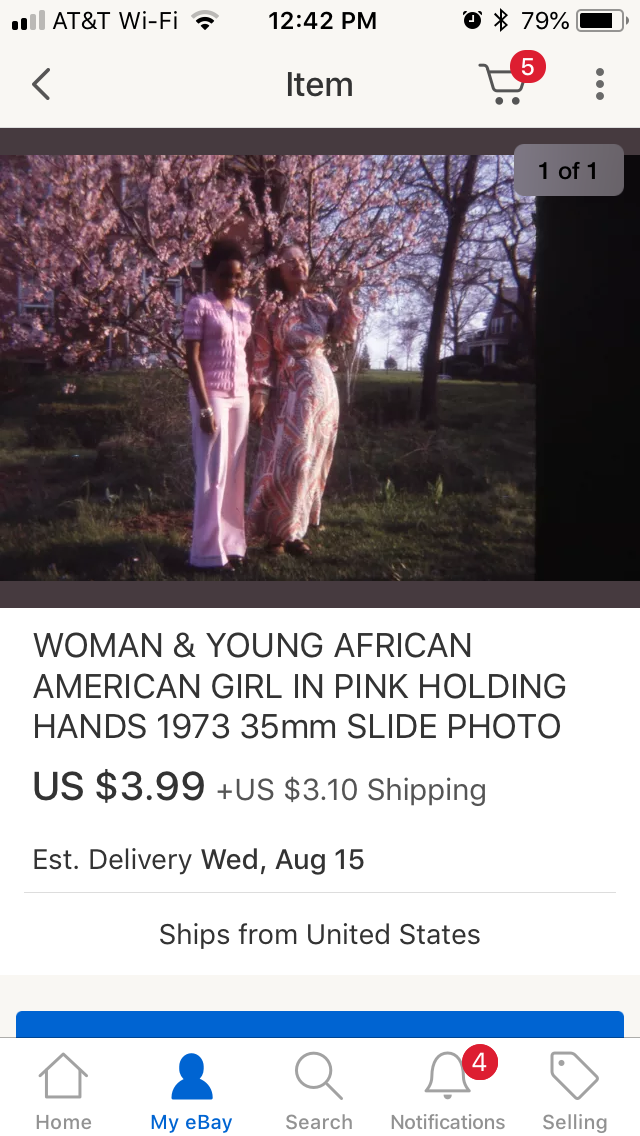

To return to my introduction, and how this informs my choices with The Picurious, I want to show you a few screenshots from eBay, which is where I acquire most of my photos for the project.

Here are two more that I want to show you to point out how the sellers described the images. Notice how “woman” and “young woman” refer to the white person in the photo while the black woman has the modifier “African American.” This reveals the assumption that underlies all of the links and text above that white skin is perceived as the default, the norm. It doesn’t need a modifier. It just is.

The fetishization of images like this on the market means they can be quite expensive, as is evident in the first trio of screenshots. The last two are more aligned with an average price for an above-average slide. I purchased the one of the women in pink, and will be giving it a new title when I release it as an art print. I also own the photo of the sailor at the top, from sometime in the 1950s, during apartheid in the United States.

Looking only at decontextualized photographs from the mid-20th century we can’t always know person’s ethnicity. In pictures, individuals of a variety of backgrounds can assimilate in a way that they may not have been able to in life. In a photo, there is no accented speech, or mother tongue. This means that other people of color, of different ethnic identities, and even of a variety of sexual preferences and gender identities may not be identifiable as such solely through a photograph.

As artist and curator of The Picurious I want to practice what I preach to my students and include compelling images with more diversity as often as possible. All of this is to say: I’m actively working on it and I can’t wait until my website more accurately reflects the democratic self-representation that photography continues to create.